Why Are the Hearings Repeating the Same Thing Over and Over Again

- Original article

- Open Access

- Published:

The effects of repetition frequency on the illusory truth effect

Cognitive Enquiry: Principles and Implications book 6, Commodity number:38 (2021) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Repeated information is ofttimes perceived every bit more than true than new information. This finding is known as the illusory truth effect, and information technology is typically idea to occur because repetition increases processing fluency. Because fluency and truth are ofttimes correlated in the existent world, people larn to use processing fluency equally a marker for truthfulness. Although the illusory truth event is a robust phenomenon, well-nigh all studies examining it take used three or fewer repetitions. To address this limitation, we conducted ii experiments using a larger number of repetitions. In Experiment one, we showed participants trivia statements upward to 9 times and in Experiment ii statements were shown upward to 27 times. Later, participants rated the truthfulness of the previously seen statements and of new statements. In both experiments, we institute that perceived truthfulness increased every bit the number of repetitions increased. However, these truth rating increases were logarithmic in shape. The largest increase in perceived truth came from encountering a argument for the second fourth dimension, and beyond this were incrementally smaller increases in perceived truth for each additional repetition. These findings add to our theoretical understanding of the illusory truth effect and take applications for advertising, politics, and the propagation of "simulated news."

Significance statement

Repetition can bear upon beliefs almost truth. People tend to perceive claims as truer if they have been exposed to them before. This is known as the illusory truth upshot, and it helps explain why advertisements and propaganda piece of work, and also why people believe fake news to be true. Although a large number of studies have shown that the illusory truth consequence occurs, very little research has used more than three repetitions. Nonetheless, in the real world, claims are ofttimes encountered at much higher repetition rates. The goal of the current research was to examine how a larger number of repeated exposures affects our judgments of truth. To do so, nosotros conducted 2 experiments. In each experiment, we asked participants to read trivia statements such equally "The gestation period of a giraffe is 425 days". In Experiment 1, the trivia statements were shown either 1, 3, 5, 7, or ix times. In Experiment 2, the trivia statements were shown either 1, 9, 18, or 27 times. One week later, we showed participants these same facts along with new facts and asked them to rate their truthfulness. In both experiments, we constitute that the more often that participants had previously encountered the trivia statement, the more truthful they rated it to be, but the largest increases in perceived truth occurred when people encountered a statement for the 2d time. Together these experiments prove the powerful event of simple repetition in affecting our judgments of truth.

The illusory truth consequence

Not everything that nosotros believe is true. For instance, according to a contempo survey of teachers in U.k. and The Netherlands, 48 percent and 46 percent, respectively, falsely believed that people only use ten percent of their brains (Dekker et al. 2012; run across likewise van Dijk and Lane 2020). Problematically, as a event of this faux belief, some people also take the misperception that "a lilliputian brain damage" is unimportant (Guilmette and Paglia 2004).

More recently, in that location has been business concern about the consequences of peoples' beliefs in misinformation, false news, and conspiracy theories about the coronavirus disease (COVID-nineteen) pandemic. In response to this health crisis, false information has been widely circulated. In fact, during the early stages of the outbreak, an analysis of posts to the social media platform Twitter showed that about a quarter of all COVID-19 tweets independent misinformation (Kouzy et al. 2020). Equally one concrete example, during the early days of outbreak, the Belgian newspaper Het Laastste Nieuws published an commodity suggesting that 5G, the cellular communication standard, might be linked to the development of COVID-nineteen. Although this idea is not supported past science, this claim has since been repeated multiple times in other forums (Ahmed et al. 2020), and a survey in the jump of 2020, showed that 5 pct of UK residents believed that the symptoms of COVID-19 were linked to 5G mobile network radiations (Allington et al. 2020). Problematically, belief in this conspiracy theory was besides associated with reduced wellness-protective behaviors (Allington et al. 2020), and since the initial newspaper article was published, there have been 77 reported attacks on cellular towers in the United kingdom and over twoscore attacks on cellular repair workers (Reichert 2020).

Why do behavior in myths, misinformation and fake news persist, despite having been clearly disproven? One contributing cistron is likely the fact that people have been exposed to this information repeatedly. Consequent with this idea, enquiry has shown that repeated data is perceived as more truthful than new information. This finding is known every bit the illusory truth effect (for a review, see Brashier and Marsh 2020) and was first reported by Hasher et al. (1977). In this experiment, participants were exposed to a list of plausible statements, some of which were true (e.one thousand., Lithium is the lightest of all metals) and some of which were false (e.1000., The capybara is the largest of the marsupials). Participants were asked to judge the truthfulness of each statement. This process was and then repeated during a second and third session. However, during these subsequent sessions, half of the statements had been previously encountered during the previous session(s), while the other one-half had not been encountered before. Results showed that with each successive session, participants rated the repeated statements every bit more than true than they had in the previous session. Furthermore, these repetition-related increases in perceived truth did not vary based upon the objective truth of the statements.

The illusory truth effect, which is sometimes as well referred to equally the repetition truth effect, has at present been replicated many times, and a meta-analysis showed that when comparison verbatim repetitions to novel information it is a medium effect size (d = 0.53; Dechêne et al. 2010). The illusory truth effect has also been demonstrated using a variety of different stimuli, including trivia statements (e.g., Bacon 1979), faux news headlines (Pennycook et al. 2018), production claims (Johar and Roggeveen 2007), opinion statements (Arkes et al. 1989), rumors (DiFonzo et al. 2016), and misinformation well-nigh observed events (Zaragoza and Mitchell 1996). The effect occurs regardless of whether the time between the repetitions is minutes (Arkes et al. 1989), weeks (Hasher et al. 1977), or even months apart (Brown and Nothing 1996). Furthermore, the effect does not depend upon the source of the statements (Begg et al. 1992) and occurs even when participants are explicitly told that the source of the statements is unreliable (Henkel and Mattson 2011) or when the initial statement had a qualifier that cast dubiety on the statement'due south validity (Stanley et al. 2019). Further bear witness of the robustness of this effect comes from studies showing that the illusory truth upshot fifty-fifty occurs when the repeated statements are highly implausible (east.g., The earth is a perfect square; Fazio et al. 2019) or when the repeated statements directly contradict participants' prior knowledge (e.thousand., The fastest land animal is the leopard; Fazio et al. 2015).

Explanations of the illusory truth effect

A diversity of different psychological explanations accept been proposed to explain why repetition increases perceived truth (for a review, see Unkelbach et al. 2019). Notwithstanding, the most commonly cited caption is the processing fluency account. Processing fluency refers to the metacognitive feel of ease or difficulty that accompanies a mental process (encounter Modify and Oppenheimer 2009). According to the processing fluency account, when information is repeated, information technology is processed more fluently and is consequently perceived to be more truthful (e.thousand., Unkelbach 2007; Unkelbach and Stahl 2009). This judgment occurs because we have learned over time that fluency (i.e., a proximal cue) is predictive of truthfulness (i.e., a more distal property that is not readily observable; Unkelbach and Greifeneder 2013). Support for the processing fluency account comes from other enquiry showing that illusions of truth tin can occur even without repetition, such that people charge per unit data presented in easy-to-read font (Reber and Schwarz 1999) or easy-to-understand speech (Lev-Ari and Keysar 2010) as existence more truthful than information presented in a less perceptually fluent format.

A further explanation of why repetition increases processing fluency comes from Unkelbach and Rom's (2017) referential theory of truth. In brief, this theory begins past noting that within a statement, the composite elements have preexisting degrees of semantic clan with 1 another. Erstwhile references are already coherently linked with one another (e.one thousand., "student" and "teacher"), only other times they are not (e.g., "sailor" and "secretary"). Nevertheless, when a statement is repeated, this repetition serves to increase the coherence between the blended reference elements. This in plow results in the statement being processed more than fluently and therefore perceived as more than truthful. Thus, co-ordinate to referential theory, processing fluency tin can be seen as an event of a retentivity network with coherent blended references (for further discussion, come across Unkelbach et al. 2019).

When contemplating how repetition will affect memory coherence and/or processing fluency, it is besides important to consider habituation effects. Habituation is a course of learning that occurs across species, and it refers to the fact that equally the number of repetitions of a given stimulus increases at that place are exponential decreases in the frequency of the associated behavioral responses (for a review see Rankin et al. 2009). Habituation also occurs at the neural level in the course of repetition suppression effects. As the number of repetitions of a given stimulus increases, there are exponential decreases in the firing rates of the neurons (for a review see Grill-Spector et al. 2006). Repetition suppression furnishings are sometimes interpreted as an index of more than fluent processing of semantic representations (e.m., Hasson et al. 2006; Henson 2003; Henson et al. 2002), which suggests that every bit the number of repetitions increases, the corresponding increases in processing fluency become incrementally smaller. This finding in plow has important implications for the perceived truth of these statements: As the number of repetitions of a argument increases, there should also be incrementally smaller increases in the perceived truth of that statement. The overarching goal of the electric current inquiry was to test this hypothesis.

Number of repetitions and perceived truth

Although a large body of enquiry has shown that repeated information is perceived equally more truthful than new information, to our knowledge only four prior studies have used more than three repetitions, and their conclusions have been mixed. Each of these prior studies is described in more particular below.

In a starting time study by Arkes et al. (1991, Experiment three), participants were asked to guess the perceived truthfulness of statements across six different report sessions. As expected, results showed that perceived truthfulness was higher in the second session equally compared to the first session. Still, pairwise comparisons of the ratings given in the subsequent adjacent written report sessions were not statistically significant. Based upon this, Arkes et al. (1991) concluded that farther repetitions practice not atomic number 82 to further increases in perceived truthfulness.

Notwithstanding, other research has suggested that larger increases in the number of repetitions tin nevertheless lead to increases in perceived truthfulness. In a study by Koch and Zerback (2013), participants were presented with the unmarried statement "microcredits reduced poverty in emerging nations" either 1, three, 5, or 7 times. These repetitions were embedded in a newspaper commodity describing an interview with the founder of the microcredit loan arrangement. Structural equation modeling suggested that this statement was perceived equally more truthful the more oftentimes that it was presented. Notwithstanding, this was obscured by the fact that in this context, repetition of this argument was also perceived to be a persuasion attempt, which in turn led to reactance and reduced belief in the argument's truth.

Finally, two other studies suggest that there may be a logarithmic human relationship between number of repetitions and perceived truth. First, Hawkins et al. (2001) observed increases in truth ratings up to 4 repetitions, merely each increment was diminished from the last. Likewise, using a greater number of repetitions, DiFonzo et al. (2016) observed increases in truth ratings up to vi repetitions (Experiments ane and 2) and 9 repetitions (Experiment 3), with each repetition-related increase once again beingness diminished from the last. However, conclusions from this study should be interpreted charily as only one statement was used per repetition condition, which may accept reduced the reliability of the mensurate. Furthermore, these statements were presented as rumors inside a narrative story, which could potentially accept been perceived every bit a persuasion tactic, and hence reduced (rather than increased) perceived truth (Koch and Zerback 2013).

Thus, although we predict that increases in the number of repetitions should pb to logarithmic increases in perceived truthfulness, previous inquiry examining this question has yielded contradictory conclusions, and the only ii studies that take used more than than 6 repetitions presented the information in a narrative context (DiFonzo et al. 2016; Koch and Zerback 2013). To farther examine this question, we conducted ii experiments that varied in the number of repetitions. In Experiment ane, the trivia statements were shown up to ix times, whereas in Experiment 2, the trivia statements were shown up to 27 times. Inside each experiment, we first tested for the presence of the illusory truth outcome (i.eastward., are repeated statements perceived as more true than new statements?). We then tested our prediction that at that place is a logarithmic (as opposed to linear) relationship between repetition frequency and truth ratings.

Experiment i

Power assay and participants

An a priori ability analysis using G*Ability iii.one that specified a matched-pair t test with an alpha level of 0.05, reported a minimum of 40 participants would exist required to achieve 90% power to observe a medium-to-large outcome of d = 0.53, which is the boilerplate outcome size of the illusory truth effect reported in a prior meta-assay (Dechêne et al. 2010). To business relationship for attrition betwixt the two written report sessions (see Process section) and information exclusions, we aimed to have 100 participants consummate Session one. Participants were recruited using Amazon Mechanical Turk through the Turk Prime platform (www.cloudresearch.com; Litman et al. 2017). There were 153 individuals who consented to participate, but just 95 completed Session 1. One week later, 78 of these participants returned, simply only 66 fully completed Session 2. Of these participants, we then excluded the 10 participants who failed 1 or more of the included attention checks (see Procedure section). This left a final sample size of 51 in the analyses reported beneath.

Participants were required to exist residents of the USA and to exist at to the lowest degree 18 years of age. The terminal sample (Thou historic period = 33.27, SD = 7.81, range 20–55) consisted of 27 men and 24 women. They self-identified their race and ethnicity equally follows: 39 identified as White or Caucasian, 9 every bit Black or African American, and three as Hispanic. Participants were besides asked nigh their highest obtained level of education: 1 reported having a Ph.D., 1000.D., or J.D., 4 reported having a Master'due south degree, nineteen reported having a 4-year college Bachelor's degree, 6 reported having a 2-year college caste, 14 reported having some higher experience, and 7 reported having a high schoolhouse diploma or equivalent.

Materials and design

Stimuli consisted of a list of 100 trivia statements. Of these, 66 statements were adaptations of the questions from Nelson and Narens norms (1980) that were previously used by both Complain et al. (1995) and by Henkel and Mattson (2011). Previous norming of this set of statements showed that they were relatively unknown, but that people perceived them as plausible (Mutter et al. 1995). Additional 34 trivia statements were constitute via online resources. These supplemental trivia statements were not normed, merely were judged by the inquiry team to as well be plausible, just relatively unknown (east.one thousand., The attachment was invented in Norway). Thus, the truthfulness of the statements used in the current research was ambiguous, which should increase the magnitude of the illusory truth issue (Fazio et al. 2019).

Whereas some prior studies have included both truthful and false statements, research has shown that repetition exerts equivalent increases in the perceived truth of previously unknown true and previously unknown simulated statements (eastward.grand., Hasher et al. 1977; Pennycook et al. 2018, Experiment ii), and repetition even increases the perceived truth of false statements that directly contradict prior knowledge (Fazio and Sherry 2020; Fazio et al. 2015). Given that the truth value of our chosen statements was expected to exist largely unknown to participants, and hence the veracity of the statements should not affect the repetition-related increases in perceived truth, we opted to only use factually accurate statements. In addition, considering it can be difficult to reduce people's conventionalities that previously encountered misinformation is true (for a review see Lewandowsky et al. 2012), our utilise of but factually accurate statements also ensured that participants did develop false beliefs every bit a result of participation in this report.

For counterbalancing purposes, the 100 trivia statements were divided into 10 sets of x statements. In doing so, we ensured that statements pertaining to particular categories (eastward.1000., geography facts) were distributed beyond the ten sets. For each participant, v sets of facts were seen during Session one and corresponded to the five repetition weather condition (i, 3, 5, vii, and nine). During the Session 2 truth ratings (see Procedure section), all 10 sets of facts were shown: Five sets of facts were new items that did non previously appear during Session 1 and the other v sets of facts were previously seen during Session i. Counterbalancing was used such that beyond all participants, each set of facts appeared equally often as a repeated and new particular, and when information technology was a repeated item, it appeared equally frequently across the five repetition conditions. This resulted in x different balanced versions of the experiment. Footnote 1

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Georgia State University (protocol H19217). Participation in this experiment consisted of two separate sessions, separated by ane calendar week. Each session was completed online, using either a computer or a mobile device.

Session 1 During Session 1, participants were randomly assigned to ane of 10 versions of the experiment, which represented the counterbalancing of specific trivia statements beyond repetition type and session (see Materials and Design section). Participants then provided consent and completed a demographics questionnaire. Participants next saw a serial of trivia statements and rated how interesting they found each statement. They were instructed that some trivia statements would be shown more than than once; however, for each argument they should charge per unit how interesting they found it at that very moment. The participants then saw the trivia statements 1 at a time in a random society. Each trial consisted of the presentation of the trivia statement for 4 south. After this, the statement disappeared from view and participants were asked to charge per unit how interesting the statement was on a scale of 1 (not interesting) to 6 (very interesting). These ratings were self-paced.

Over the form of this Session 1 task, participants saw 50 statements. Each statement was presented either one, 3, five, 7, or ix time(s) and in total there were x statements in each repetition status. This made for 250 trials. Additionally, three attention check trials were as well included. These attention check trials simply stated: Please select X for the next rating, with 10 being either the answer choice of 1, 2, or 3. The order of the 253 trials was randomized (although the precise randomization order that was used for each participant was non recorded). On boilerplate, participants spent 54.87 min completing the Session 1 tasks and were compensated $4.l for their participation.

Session 2 Consistent with previous research (east.g., Arkes 1989; Boehm 1994; Fazio et al. 2015), one week afterward participants were invited to complete a second written report session. During Session 2, participants were shown our entire listing of 100 statements. Of these, 50 had been previously seen during Session ane and 50 were new statements. Nosotros chose to use a mixed-list of repeated and new facts every bit this should create variability in the fluency of the statements, which should increment the likelihood of observing illusory truth furnishings (e.1000., Dechene et al. 2009; Garcia-Marques et al. 2019). The 100 statements were presented in a random gild, 1 at a time, and participants were asked to rate how truthful they found each statement on a scale of 1 (non truthful) to half-dozen (very true). Participants were instructed that we were interested in their own perceptions well-nigh the truthfulness of the statements, and were told not to await upwardly whatsoever of the statements while completing the task. During Session two, two attention cheque trials, similar to those used in Session one, were also included. On average, participants spent thirteen.78 min completing the Session two tasks and were compensated $3.50 for their participation.

Results

We first evaluated whether or not nosotros replicated the illusory truth effect. As in prior research, in a matched-pair t test, we establish that repeated statements elicited college truth ratings (M = 4.49, SD = 0.60; collapsing beyond repetition conditions) compared to the never-earlier-seen statements (M = 3.76, SD = 0.67), t(50) = 7.sixteen, p < 0.001, d = ane.00. Footnote 2

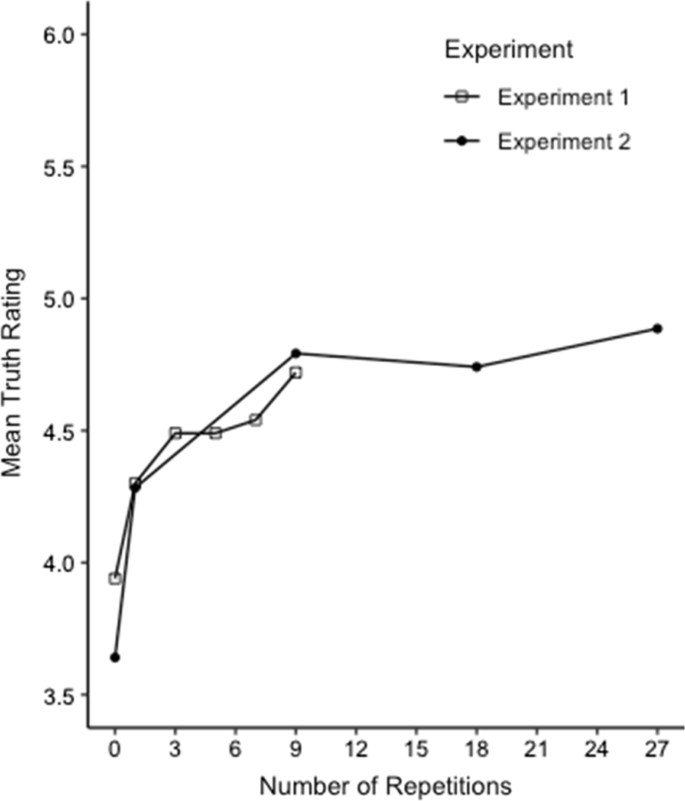

Nosotros adjacent evaluated our hypothesis that there would be a logarithmic (as opposed to linear) relationship between the number of times a statement was repeated during Session one and perceptions of truth during Session 2. To do so, for each participant nosotros calculated the correlation coefficient betwixt their Session two truth ratings and the number of Session ane repetitions (0, 1, 3, v, seven, nine), and too between their Session ii truth ratings and the log of the number of Session ane repetitions (for a similar procedure, come across Guild et al. 2014). In both cases, we added a constant of 1 to the number of Session 1 repetitions, to account for the fact that the log of 0 is undefined. Footnote 3 On boilerplate, truth ratings had a moderate-to-large correlation with the linear scaling of the Session 1 repetitions (mean r = 0.46, SD = 0.43; range of rsouth = -0.72 to 0.93; correlations were greater than zip for 88% of participants). Truth ratings also had a large correlation with the logarithmic scaling of the Session i repetitions (mean r = 0.52, SD = 0.44, range of rs = -0.57 to 0.98; correlations were greater than zero for 84% of participants). All the same, a matched pair t-test showed that the magnitude of the correlation was significantly greater when using the logarithmic scale, equally compared to the linear scale, t(50) = 4.83, p < 0.001, d = 0.67 (see Fig. 1).

Mean Truth Ratings as a Function of Number of Repetitions in Experiment i and Experiment ii

As shown in Tabular array ane, follow-up Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons showed that in that location were large differences in perceived truth betwixt the never-before-seen items and the previously seen items. The new statements were rated as significantly less truthful than statements in the ane, 3, 5, 7, and nine repetition conditions (i.e., at that place was an illusory truth consequence). All the same, there were fewer significant differences between items from the other repetition weather condition. In fact, the only other significant pairwise comparison was between statements in the 1 and 9 repetition weather condition.

Experiment ii

Although Experiment one showed that increased repetitions were associated with logarithmic increases in truth ratings, one limitation of this study is that our maximum number of repetitions was nine. To address this, in Experiment 2 we repeated the facts either 1, 9, xviii, or 27 times. We chose intervals of nine repetitions because the Experiment 1 results showed a meaning deviation in the perceived truthfulness of items previously presented once versus nine times.

In Experiment 2, we also express our sample to younger adults, aged xviii to 35. Prior research has shown that older adults demonstrate greater illusory truth effects than younger adults (Law et al. 1998). Replicating this, in Experiment 1 we as well establish that the difference in truth ratings between quondam and new items was larger with increasing age, F(1, 49) = 7.05, p = 0.011, η p 2 = 0.13. Although none of the Experiment 1 conclusions alter when including historic period as a cistron (i.e., regardless of whether participants were relatively older or relatively younger, in Experiment ane the logarithmic scale was more strongly related to truth ratings than the linear scale), to reduce variability in illusory truth furnishings, in Experiment 2 we limited our sample to individuals aged 18 to 35.

Participants

Using the aforementioned recruitment strategies as in Experiment i, there were 151 individuals consented to participate in Experiment 2, just only 100 completed Session 1. One calendar week later, 70 of these participants returned, only only 64 fully completed Session 2. As in Experiment 1, we then excluded the seven participants who failed one or more of the included attending checks (see Process department). This left a terminal sample size of 57 in the analyses reported below.

Participants were required to exist residents of the USA, aged 18 to 35. Within the last sample, participants were on average 29.46 years former (SD = iii.49, range 21–35). Although all participants reported their age, due to experimenter error we did not assess gender, racial identity, or educational attainment in all viii of the counterbalanced versions of the experiment (see Materials and Design section). Gender was only assessed in two versions: Of participants asked this question there were 8 men and viii women. Race was assessed in vii versions, with these participants cocky-identifying as follows: 38 as White or Caucasian, 5 as Black or African American, three as Asian, i as American Indian or Alaska Native, 1 as Biracial, and two did not identify with any of the provided racial identity choices. Educational attainment was simply assessed in two versions: Of participants asked this question half dozen reported having a 4-year college Bachelor's degree, 2 reported having a ii-yr higher caste, 3 reported having some college experience, 5 reported having a loftier school diploma or equivalent, and one reported having some high school.

Materials and design

The list of 100 statements used in Experiment 1 was pared downwardly to 64 statements. This was done pseudorandomly with the constraint that we maintained variety in the broad categories of trivia facts represented. For instance, we ensured that we were not discarding all of the statements related to animals or all of the statements related to geography. The statements were then divided into 8 sets of viii statements. For each participant, four sets were used during Session ane and corresponded to the four repetition types (1, 9, xviii, and 27). The other four sets were used every bit new items during Session two. Counterbalancing was used such that across participants, each set appeared equally oftentimes as a repeated or new items, and when it appeared every bit a repeated item, appeared equally often beyond the four repetition types. This resulted in eight different balanced versions of the experiment.

Procedure

The procedure for Experiment ii was approved past the IRB at Georgia State Academy (protocol H19217) and was identical to Experiment i with the following exceptions. First, the ratings during Session 1 were non self-paced. In lodge to standardize the amount of time spent viewing the statements, participants were given 4 s to view each fact, followed by 4 s to charge per unit their current interest in the fact.

2nd, as noted higher up (see Materials and Design), during Session 1 of Experiment 2 the statements were presented either ane, ix, eighteen, or 27 time(s). Equally there were 8 statements in each repetition status, this fabricated for 440 critical trials. With the add-on of 3 attending trials, the total number of trials was 443 (as opposed to 253 in Experiment one).

Third, at the end of Session 2 we also asked participants whether they had looked up, or discussed with others, any of the Session 1 facts during the prior calendar week. Just 3 participants reported having done so, and these participants further reported that this affected two or fewer of the Session 1 facts. Excluding these participants did non change any of the reported patterns of results, and hence, they were retained in the subsequent analyses.

On average, participants spent 68 min completing Session 1 and 13.84 min completing Session 2 and compensated $7.25 and $iii.75, respectively. Footnote four

Results

We showtime tested for the illusory truth effect using a matched-pairs t test. Results showed that the repeated statements (Yard = 4.66, SD = 0.86; collapsing across repetition conditions) elicited higher truth ratings compared to never-before-seen statements (M = three.64, SD = 0.65), t(56) = 8.22, p < 0.001, d = i.09.

We next tested our hypothesis that there would exist a logarithmic (as opposed to linear) human relationship betwixt the number of times a argument was repeated during Session 1 and perceptions of truth during Session 2. Equally in Experiment 1, we correlated each participants' average truth ratings during Session 2 with both the number of Session 1 repetitions (0, 1, ix, 18, 27), as well every bit with the log of the number of Session 1 repetitions. In both cases, we added a constant of 1 to the number of Session one repetitions, to account for the fact that the log of 0 is undefined. As in Experiment one, truth ratings tended to have a moderate-to-big correlation with the linear scaling of the Session 1 repetitions (hateful r = 0.47, SD = 0.43; range of rs = -0.84 to 0.95; correlations were greater than zero for 82% of participants). Truth ratings besides tended to have a moderate-to-big correlation with the logarithmic scaling of the Session 1 repetitions (mean r = 0.56, SD = 0.44, range of rsouthward = -0.82 to 0.99; correlations were greater than zero for 86% of participants). Even so, a matched-pair t test showed that the showed that magnitude of the correlation was significantly greater when using the logarithmic scale, as compared to the linear calibration, t(56) = eight.22, p < 0.001, d = 0.63 (see Fig. 1)

As shown in Table 2, this determination was farther supported by follow-upwards Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons. Here, we found that new statements were rated as less true than those previously seen ane, ix, 18, or 27 times. However, there were very few statistically meaning differences between items from the other repetition conditions. Statements in the i repetition status were rated significantly less truthful than statements in the 9, xviii, and 27 repetition atmospheric condition. However, no other comparisons between repetition conditions were found to be statistically significant.

Discussion

The goal of this inquiry was to examination the hypothesis that the more frequently data is encountered, the more truthful that information is perceived to be, and that this relationship is logarithmic in nature. To exam this, we asked participants to read trivia statements, which were repeated up to ix times in Experiment ane and upwards to 27 times in Experiment 2. One calendar week afterward, participants saw these aforementioned trivia statements alongside the new statements and were asked to guess the truthfulness of each statement. As expected, in both experiments we replicated the illusory truth effect such that repeated statements were perceived every bit more truthful than new statements. We as well plant that perceived truthfulness increased as the number of repetitions increased, and in line with our predictions, these increases were logarithmic in nature. In both experiments, the largest increases in perceived truth came from encountering a statement for the second time. However, across this, there were progressively smaller increases in perceived truth for each boosted repetition, which were not statistically meaning beyond 9 repetitions.

These findings back up the predictions based upon both the processing fluency account and also based upon the referential theory of truth. They are also consequent with enquiry by Hawkins et al. (2001) who found that repeating information up to iv times results in progressively smaller increases in truth ratings. As well, DiFonzo et al. (2016) found a logarithmic relationship, such that repeating information up to ix times also results in progressively smaller increases in truth ratings. We replicate their findings using a larger number of items outside of a narrative context (Experiment one) and extend their results past showing that this blueprint continues upwardly to at least 27 repetitions (Experiment 2).

In addition, our results—just not our conclusions—are also consistent with those reported by Arkes et al. (1991, Experiment three). Every bit in their study, we found that fifty-fifty though information shown for the 2d fourth dimension was rated as significantly more than true than new information, pairwise comparisons of truth ratings for the subsequent repetition weather were rarely statistically significant. For example, in our Experiment 1, the truth ratings for the statements presented iii times did non significantly differ from the truth ratings for the statements presented five times (run across Tables 1, 2). Based upon similar null results, Arkes et al. (1991) ended that while a first repetition increases perceived truth, subsequent repetitions practice not. In contrast, we conclude that while a first repetition produces the largest increase in perceived truth, subsequent repetitions produce subsequent increases in truth that are incrementally macerated in size. As a event, statistically significant increases in perceived truth may only occur after a large number of additional repetitions. Furthermore, because a logarithmic function has no asymptote, theoretically, information technology stands to reason that repetitions will elicit higher and higher truth ratings indefinitely. However, at some signal these incremental increases in perceived truth will become so small-scale in magnitude that they no longer have practical value.

Agreement the applied value of increased repetitions is important considering the illusory truth effect affects important daily life decisions (for farther word, run across Unkelbach et al. 2019) and our findings are highly relevant inside the realms of politics and "fake news." For example, using actual fake-news headlines from the 2016 US presidential election, Pennycook et al. (2018) establish that the more often that participants were exposed to these headlines, the more likely they were to believe them to be truthful. This occurred fifty-fifty when the headlines were clearly tagged as being false facts, and when their content was inconsistent with the participants' ain political ideology. Although this demonstrates that a single encounter with a faux news story will make it seem more truthful, in our daily lives we sometimes encounter faux information repeatedly. For example, during his 2016 campaign to be elected as President of the USA, Donald Trump stated 86 times that the structure of a wall between the U.s. and Mexico had already begun (see Murray et al. 2020). Although this was false, our results advise that each fourth dimension this claim was repeated, its perceived truthfulness incrementally increased.

These results are besides relevant for understanding the public'due south response to the COVID-xix pandemic: Our results advise that the more frequently letters about COVID-nineteen are repeated, the more true they will be perceived. The consequences of this tin be positive or negative, depending upon the validity of the messages. An example of this comes from Bursztyn, Rao, Roth, and Yanagizawa-Drott'south (2020) analyses of the relationship between viewers' health outcomes and the coverage of COVID-19 they had seen on Hannity and Tucker Carlson Tonight. Although these cable news shows are both circulate on Pull a fast one on News, beginning in early on Feb of 2020, Carlson warned viewers that COVID-19 might pose a serious wellness threat to the USA. In dissimilarity, Hannity originally claimed that COVID-19 was no different than the flu and was being used by Democrats equally a political weapon. Hannity only began to describe COVID-19 every bit a threat in mid-March of 2020. Being exposed to these repeated messages was associated with adverse health outcomes for the Hannity viewers. In a survey of Fox News viewers anile 55 of older in April 2020, a one standard difference college viewership of Hannity (relative to Carlson) was associated with 33% more COVID-19 cases on March 14th, and 34% more COVID-19 deaths on April fourth. Presumably this occurred because the messages about COVID-xix had been repeatedly presented on the news, and were believed by the viewers. This in plough may have had a ripple effect, equally people are also more likely to share with others information that they have repeatedly encountered (Effron and Raj 2020).

A terminal domain for which the electric current experiments' findings are relevant is advertising. Prior research has shown that repeated advertisements are associated with people perceiving the advertised production as college in quality (Moorthy and Hawkins 2005), and our results suggest that it may likewise increase perceived truth of the advertizing message. However, one cistron that often moderates advertizing repetition furnishings is the number of advertisements (e.m., Burton et al. 2019; Kohli et al. 2005). For instance, results of a meta-analysis advise that at that place are increases in positive attitudes with up to 10 exposures of an advertisement, after which there are decreases in positive attitudes (Schmidt and Eisend 2015). The terms "clothing-in" and "wearable-out" are used to describe these furnishings. An advertising is "worn in" when the repetition initially garners a positive effect and is "worn out" when the repetition produces no effect or even a negative i (Pechmann and Stewart 1988).

Consistent with this idea, data from Experiment 2 propose that repetition-related increases in perceived truth may be "worn out" after 9 repetitions. Every bit shown in Fig. 1, after nine repetitions the truth ratings appear to arroyo an asymptote, and later on this point the practical value of further repetitions may be limited. Although we did not observe whatever evidence that repetitions across this negatively touch on perceived truth, it is possible that an changed U-shape may have occurred if we had used a persuasion context (such every bit would occur during advert). This is consistent with prior research from Koch and Zerback (2013). As previously described, participants in this report read a newspaper interview with the founder of microcredit loans. Embedded in this interview was the argument "microcredits reduced poverty in emerging nations," which was repeated either one, three, five, or seven times. Results from a structural equation model suggested that increased repetitions pb to increased belief that microcredit loans decrease poverty in emerging nations. Yet, increased repetitions also led participants to trust the communicator less, and to believe that the message was a persuasion endeavour. Every bit a outcome, participants who heard statements multiple times interpreted the reason for those repetitions as an intent to persuade them, and demonstrated reactance by rating the statement lower in truthfulness.

It is likewise possible that nosotros did non observe an inverse U-shaped bend because nosotros did not include a sufficient number of repetitions. Support for this possibility comes from enquiry on the mere-exposure effect. This is the finding that repeated exposure to an initially neutral and unfamiliar stimulus results in greater liking of that stimulus (Zajonc 1968), and this is thought to reflect repetition-related increases processing fluency (Reber and Schwarz 2001; Reber et al. 1998). However, a meta-assay shows that the relationship betwixt repetition and liking resembles an inverted U-shaped curve. More than specifically, liking continues to increase up to about 62 repetitions, simply after this betoken additional repetitions pb to declines in liking (Montoya et al. 2017; see as well Bornstein and D'Agostino 1992). If a peak in perceived truth occurs after a like number of repetitions, the current experiments would not take observed it. Statements were repeated a maximum of 9 times in Experiment one and 27 times in Experiment 2. Thus, futurity research examining the relationship between repetition and perceived truth should include an fifty-fifty greater number of repetitions.

Futurity studies should also address the limitations that were nowadays in these experiments. The beginning being that we did not assess whether or non any of the statements included were previously known to each participant. While we could accept assessed pre-experimental knowledge of the facts, it has been shown that prior cognition does non shield one from the illusory truth effect (Fazio et al. 2015). Information technology is therefore probable that the patterns reported here would take emerged even for misinformation or simulated news that contradicted prior knowledge.

A second limitation has to do with the presentation and length of the study sessions. In these studies, participants read trivia statements in black text on a white background for over an hr on their phones or computers. This may have contributed to mind-wandering and colorlessness, and even though all participants included in analyses passed our attention checks, they may not have given the statements their full attention. This reduced attentiveness may actually have maximized the illusory truth effects that were observed. For instance, Hawkins and Hoch (1992) constitute what they termed "low-involvement" learning was a key factor to observing the illusory truth upshot. When participants were exposed to advertisement statements, those who engaged in the "low-involvement" learning task (i.e., those who were asked to rate the statements based on how piece of cake they were to understand) experienced stronger subsequent illusory truth effects than those in the "high-involvement" learning job (i.e., those who were asked to rate statements based on how truthful they were). It appears that deeper date while processing the statement can protect one from repetition-based illusory truth effects. Consistent with this, Brashier et al. (2020) recently found that participants who were actively involved in "fact-checking" the presented statements showed a reduced illusory truth effect (at least when they had the requisite knowledge to perform the job).

A final limitation is that we did not examine the role of repetition spacing in modulating the magnitude of the illusory truth effect. In the current experiments, the trivia facts (and their repetitions) were presented in a random order for each participant during the first report session, simply unfortunately these randomization orders were not recorded. Given prior research showing that neural repetition suppression is reduced for spaced, equally compared to massed, repetitions (eastward.1000., Xue et al. 2011), it is reasonable to hypothesize that illusory truth effects should also be greater following spaced, as compared to massed, repetitions. Preliminary results from our laboratory support this hypothesis (Barber et al. 2020), and ongoing research is now examining the combined influence of the number of repetitions and the spacing of those repetitions in affecting perceived truth.

In summary, our results suggest that the more ofttimes information is repeated, the more probable it is to exist believed. This is important since we frequently encounter information whose validity is unknown. Although believing repeated information to exist true is evolutionarily efficient in a context where about of the data encountered is correct, it can be detrimental to believe data that is incorrect. Sometimes these consequences can be trite: If you are repeatedly shown the faux statement "Salty water boils faster," yous may come to believe this to be true. Nonetheless, acting on this faux belief volition only slightly elongate your cooking fourth dimension. In contrast, other times the consequences can be life-threatening: If y'all are repeatedly told that "COVID-19 is no more than dangerous than the common common cold," you may come up to believe this to be truthful, only acting on this simulated conventionalities may increase your take chances of infection and death. Although our studies did not use fake news, conspiracy theories, or misinformation for stimuli, our results shed light on the mechanism underlying illusory truth furnishings, and propose that repeated exposures probable lead to increased belief. In addition, our results suggest that the largest increases in perceived truth come from hearing information a 2d time. Going beyond this, subsequent repetitions pb to progressively smaller increases in perceived truth. Nonetheless, later 9 repetitions these increases may no longer exist practically meaningful.

Availability of information and materials

Data and study materials are bachelor from the corresponding author upon asking.

Notes

-

Due to attrition and data exclusions, the counterbalanced versions of the statements were non evenly represented in the final samples of Experiment 1 or Experiment 2. However, when including counterbalance version number as a factor in analyses, there were no chief effects or interactions to report. In addition, the sets of facts did non significantly differ in the truth ratings they received the first fourth dimension they were shown. Weigh version volition therefore non be discussed farther.

-

Every bit a concrete example, presume that a participant's average truth rating for the new items (seen 0 times during Session one) was 3.75. Besides assume that this aforementioned participant'due south average truth ratings for the repeated items were iv.6, 5.9, 6.0, v.7, and vi.0 for items seen ane, 3, 5, vii, and 9 times during Session ane, respectively. Calculation a abiding of 1 to each repetition condition, this participant's truth ratings would have a correlation of r = .80 with the linear number of Session 1 repetitions (1, 2, 4, six, 8, 10), but a correlation of r = .93 with the log of the number of Session 1 repetitions (one, 0.30, 0.60, 0.78, 0.90, 1.0).

-

In Experiment 1, participants took longer than expected to complete Session 1. In Experiment 2 we standardized the corporeality of time spent rating the Session 1 statements, and increased the compensation to improve reflect the corporeality of fourth dimension that participants spent completing the task.

References

-

Ahmed, W., Vidal-Alaball, J., Downing, J., & Seguí, F. 50. (2020). COVID-xix and the 5G conspiracy theory: Social network analysis of Twitter data. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22, e19458. https://doi.org/10.2196/19458

-

Allington, D., Duffy, B., Wessely, S., Dhavan, N., & Rubin, J. (2020). Health protective behaviour, social media usage, and conspiracy belief during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Psychological Medicine,. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000224X

-

Alter, A. L., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2009). Uniting the tribes of fluency to form a metacognitive nation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13, 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309341564

-

Arkes, H. R., Boehm, 50. E., & Xu, G. (1991). Determinants of judged validity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 27, 576–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(91)90026-iii

-

Arkes, H. R., Hackett, C., & Boehm, 50. (1989). The generality of the relation betwixt familiarity and judged validity. Journal of Behavioral Determination Making, 2, 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.3960020203

-

Bacon, F. T. (1979). Credibility of repeated statements: Memory for trivia. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 5, 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.5.3.241

-

Barber, South. J., Hassan, A., & White, S. (2020, November 20). Perceived truth as a part of the number and spacing of repetitions. Newspaper presented at the 61st almanac meeting of the Psychonomic Club. Online event due to COVID-19.

-

Begg, I. M., Anas, A., & Farinacci, S. (1992). Dissociation of processes in belief: source recollection, argument familiarity, and the illusion of truth. Periodical of Experimental Psychology: Full general, 121, 446–458. https://doi.org/x.1037/0096-3445.121.iv.446

-

Bornstein, R. F., & D'Agostino, P. R. (1992). Stimulus recognition and the mere exposure outcome. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 545–552. https://doi.org/x.1037/0022-3514.63.four.545

-

Brashier, Northward. M., Eliseev, E. D., & Marsh, E. J. (2020). An initial accuracy focus prevents illusory truth. Cognition, 194, 104054. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.cognition.2019.104054

-

Brashier, N. Chiliad., & Marsh, East. J. (2020). Judging truth. Annual Review of Psychology, 71, 499–515. https://doi.org/ten.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050807

-

Brown, A. Southward., & Nix, L. A. (1996). Turning lies into truths: Referential validation of falsehoods. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 22, 1088–1100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.22.5.1088

-

Bursztyn, L., Rao, A., Roth, C., & Yanagizawa-Drott, D. (2020). Misinformation during a pandemic.University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Newspaper No. 2020–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3386/w27417

-

Burton, J. L., Gollins, J., McNeely, L. E., & Walls, D. M. (2019). Revisiting the relationship betwixt ad frequency and buy intentions: How touch on and cognition mediate outcomes at different levels of advertising frequency. Journal of Advertising Inquiry, 59, 27–39. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2018-031

-

Dechêne, A., Stahl, C., Hansen, J., & Wänke, M. (2010). The truth about the truth: A meta-analytic review of the truth effect. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14, 238–257. https://doi.org/x.1177/1088868309352251

-

Dekker, S., Lee, N. C., Howard-Jones, P., & Jolles, J. (2012). Neuromyths in Education: Prevalence and Predictors of Misconceptions amongst Teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, iii, 429. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00429

-

DiFonzo, N., Beckstead, J. West., Stupak, N., & Walders, Chiliad. (2016). Validity judgments of rumors heard multiple times: The shape of the truth effect. Social Influence, 11, 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2015.1137224

-

van Dijk, West., & Lane, H. B. (2020). The brain and the United states of america educational activity organisation: Perpetuation of neuromyths. Exceptionality, 28, 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09362835.2018.1480954

-

Effron, D. A., & Raj, M. (2020). Misinformation and morality: Encountering fake-news headlines makes them seem less unethical to publish and share. Psychological Science, 31, 75–87. https://doi.org/ten.1177/0956797619887896

-

Fazio, L. Chiliad., Brashier, N. M., Payne, B. K., & Marsh, E. J. (2015). Knowledge does not protect against illusory truth. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144, 993–1002. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000098

-

Fazio, L. Chiliad., Rand, D. Thou., & Pennycook, Yard. (2019). Repetition increases perceived truth equally for plausible and implausible statements. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 26, 1705–1710. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-019-01651-4

-

Fazio, 50. 1000., & Sherry, C. Fifty. (2020). The upshot of repetition on truth judgments across development. Psychological Science, 31, 1150–1160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620939534

-

Garcia-Marques, T., Silva, R. R., Mello, J., & Hansen, J. (2019). Relative to what? Dynamic updating of fluency standards and between-participants illusions of truth. Acta Psychologica, 195, 71–79. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.actpsy.2019.02.006

-

Grill-Spector, Yard., Henson, R., & Martin, A. (2006). Repetition and the brain: Neural models of stimulus-specific effects. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10, xiv–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.11.006

-

Club, E. B., Cripps, J. M., Anderson, North. D., & Al-Aidroos, N. (2014). Recollection can support hybrid visual memory search. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21, 142–148. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-013-0483-iii

-

Guilmette, T. J., & Paglia, M. F. (2004). The public'south misconceptions virtually traumatic encephalon injury: A follow-up survey. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 19, 183–189. https://doi.org/ten.1016/S0887-6177(03)00025-8

-

Hasher, L., Goldstein, D., & Toppino, T. (1977). Frequency and the briefing of referential validity. Journal of Exact Learning and Verbal Beliefs, 16, 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(77)80012-1

-

Hasson, U., Nusbaum, H. C., & Small, S. L. (2006). Repetition suppression for spoken sentences and the effect of chore demands. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 18, 2013–2029. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2006.xviii.12.2013

-

Hawkins, S. A., & Hoch, South. J. (1992). Low-involvement learning: Retentiveness without evaluation. Journal of Consumer Research, xix, 212–225. https://doi.org/10.1086/209297

-

Hawkins, Southward. A., Hoch, South. J., & Meyers-Levy, J. (2001). Low-involvement learning: Repetition and coherence in familiarity and belief. Periodical of Consumer Psychology, 11, i–11. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327663JCP1101_1

-

Henkel, L. A., & Mattson, M. E. (2011). Reading is believing: The truth result and source credibility. Consciousness and Cognition, 20, 1705–1721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2011.08.018

-

Henson, R. Northward. (2003). Neuroimaging studies of priming. Progress in Neurobiology, seventy, 53–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-0082(03)00086-8

-

Henson, R. Due north. A., Shallice, T., Gorno-Tempini, M. L., & Dolan, R. J. (2002). Confront repetition effects in implicit and explicit memory tests as measured by fMRI. Cerebral Cortex, 12, 178–186. https://doi.org/x.1093/cercor/12.two.178

-

Johar, G. V., & Roggeveen, A. L. (2007). Changing simulated behavior from repeated advertising: The part of claim-refutation alignment. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-7408(07)70018-9

-

Koch, T., & Zerback, T. (2013). Helpful or harmful? How frequent repetition affects perceived statement credibility. Journal of Communication, 63, 993–1010. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12063

-

Kohli, C. S., Harich, M. R., & Leuthesser, L. (2005). Creating make identity: a study of evaluation of new brand names. Journal of Business concern Research, 58, 1506–1515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2004.07.007

-

Kouzy, R., Jaoude, J. A., Kraitem, A., El Alam, M. B., Karam, B., Adib, E., Zarka, J., Traboulsi, C., Akl, E. W., & Baddour, Thou. (2020). Coronavirus goes viral: Quantifying the COVID019 misinformation epidemic on Twitter. Cureus, 12, e7255. https://doi.org/x.7759/cureus.7255

-

Law, S., Hawkins, South. A., & Craik, F. I. (1998). Repetition-induced belief in the elderly: Rehabilitating age-related memory deficits. Journal of Consumer Research, 25, 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1086/209529

-

Lev-Ari, S., & Keysar, B. (2010). Why don't we believe non-native speakers? The influence of emphasis on credibility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 1093–1096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.05.025

-

Lewandowsky, South., Ecker, U. K., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Melt, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Scientific discipline in the Public Involvement, 13, 106–131. https://doi.org/ten.1177/1529100612451018

-

Litman, L., Robinson, J., & Abberbock, T. (2017). TurkPrime.com: A versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioral sciences. Beliefs Enquiry Methods, 49, 433–442. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0727-z

-

Montoya, R. M., Horton, R. South., Vevea, J. L., Citkowicz, 1000., & Lauber, E. A. (2017). A re-examination of the mere exposure effect: The influence of repeated exposure on recognition, familiarity, and liking. Psychological Message, 143, 459–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000085

-

Moorthy, S., & Hawkins, S. A. (2005). Advertizing repetition and quality perception. Periodical of Business organization Research, 58, 354–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(03)00108-5

-

Murray, S., Stanley, M., McPhetres, J., Pennycook, G., & Seli, P. (2020). " I've said information technology before and I will say information technology once again": Repeating statements made by Donald Trump increases perceived truthfulness for individuals across the political spectrum. Unpublished manuscript. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/9evzc

-

Mutter, Due south. A., Lindsey, S. Eastward., & Pliske, R. M. (1995). Aging and credibility judgment. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Knowledge, ii, 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825589508256590

-

Nelson, T., & O., & Narens, L. . (1980). Norms of 300 general-information questions: Accuracy of recall, latency of recall, and feeling-of-knowing ratings. Periodical of Verbal Learning and Verbal Beliefs, 19, 338–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(80)90266-two

-

Pechmann, C., & Stewart, D. West. (1988). Advertisement repetition: A disquisitional review of wearin and wearout. Current Bug and Research in Advertising, 11, 285–329.

-

Pechmann, C., & Stewart, D. W. (1990). The effects of comparative advertizing on attention, memory, and buy intentions. Journal of Consumer Research, 17, 180–191. https://doi.org/ten.1086/208548

-

Pennycook, G., Cannon, T. D., & Rand, D. One thousand. (2018). Prior exposure increases perceived accuracy of faux news. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147, 1865–1880. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000465

-

Rankin, C. H., Abrams, T., Barry, R. J., Bhatnagar, South., Clayton, D. F., Colombo, J., & McSweeney, F. K. (2009). Habituation revisited: An updated and revised description of the behavioral characteristics of habituation. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 92, 135–138. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.nlm.2008.09.012

-

Reber, R., & Schwarz, Due north. (1999). Furnishings of perceptual fluency on judgments of truth. Consciousness and Knowledge, 8, 338–342. https://doi.org/x.1006/ccog.1999.0386

-

Reber, R., & Schwarz, Northward. (2001). The hot fringes of consciousness: Perceptual fluency and affect. Consciousness & Emotion, 2, 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1075/ce.two.2.03reb

-

Reber, R., Winkielman, P., & Schwarz, North. (1998). Effects of perceptual fluency on affective judgments. Psychological Science, 9, 45–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00008

-

Reichert, C. (2020, July 23). 5G coronavirus conspiracy theory leads to 77 mobile towers burned in UK, study says. Retrieved from https://www.cnet.com/health/5g-coronavirus-conspiracy-theory-sees-77-mobile-towers-burned-study-says/

-

Schmidt, Southward., & Eisend, M. (2015). Advertising repetition: A meta-assay on effective frequency in advertising. Periodical of Advertising, 44, 415–428. https://doi.org/ten.1080/00913367.2015.1018460

-

Stanley, M. L., Yang, B. West., & Marsh, Due east. J. (2019). When the unlikely becomes likely: Qualifying language does non influence subsequently truth judgments. Periodical of Applied Enquiry in Retention and Cognition, 8, 118–129. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.jarmac.2018.08.004

-

Temperton, J. (2020, April 09). How the 5G coronavirus conspiracy theory tore through the cyberspace. Retrieved July xix, 2020, from https://world wide web.wired.co.uk/commodity/5g-coronavirus-conspiracy-theory

-

Unkelbach, C. (2007). Reversing the truth effect: Learning the interpretation of processing fluency in judgments of truth. Periodical of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Retention, and Cognition, 33, 219–230. https://doi.org/x.1037/0278-7393.33.ane.219

-

Unkelbach, C., Koch, A., Silva, R. R., & Garcia-Marques, T. (2019). Truth by repetition: Explanations and implications. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(three), 247–253. https://doi.org/ten.1177/0963721419827854

-

Unkelbach, C., & Rom, Southward. C. (2017). A referential theory of the repetition-induced truth event. Cognition, 160, 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2016.12.016

-

Unkelbach, C., & Stahl, C. (2009). A multinomial modeling approach to dissociate different components of the truth effect. Consciousness and Noesis, xviii, 22–38. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.concog.2008.09.006

-

Unkelbach, C., & Greifeneder, R. (2013). A general model of fluency effects in judgment and decision making. In C. Unkelbach & R. Greifender (Eds.) The experience of thinking: How the fluency of mental processes influences cognition and beliefs (pp. 11–32). New York, NY: Psychology Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203078938

-

Xue, G., Mei, L., Chen, C., Lu, Z. L., Poldrack, R., & Dong, Q. (2011). Spaced learning enhances subsequent recognition retentivity past reducing neural repetition suppression. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23, 1624–1633. https://doi.org/x.1162/jocn.2010.21532

-

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, i–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025848

-

Zaragoza, Chiliad. S., & Mitchell, Thousand. J. (1996). Repeated exposure to suggestion and the creation of false memories. Psychological Scientific discipline, 7, 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00377.x

Acknowledgements

Non applicable.

Funding

Publication costs were paid by Georgia State Academy. Participant compensation came from departmental funds, provided to the S.J.B.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

Data reported in this manuscript served as the basis of the A.H.'s Yard.A. thesis under the supervision of S.J.B. The ii authors contributed equally to the blueprint of the studies. A.H. programmed the experiments, performed initial data analyses, and prepared the offset draft of this manuscript. The second author provided consultation on each of these steps and too contributed substantially to the preparation of this manuscript for publication. All authors read and canonical the last manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Lath (IRB) at Georgia Land University (protocol H19217). Participants provided informed consent earlier offset the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher'due south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatsoever medium or format, as long equally you give appropriate credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons licence, and signal if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article'southward Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article'due south Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hassan, A., Barber, South.J. The effects of repetition frequency on the illusory truth effect. Cogn. Research six, 38 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00301-five

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s41235-021-00301-5

Keywords

- Illusory truth

- Repetition

- Fluency

- Belief

- Truthfulness

Source: https://cognitiveresearchjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41235-021-00301-5

0 Response to "Why Are the Hearings Repeating the Same Thing Over and Over Again"

Postar um comentário